When my husband and I decided to stay in Philadelphia after graduating from college, we always got the same questions: “Are you going to stay in the city long term?” “What will you do when you have children?” “Where will you send your kids to school?” In our mid-20s, living in the city was fun. We played in a band and loved taking advantage of all that the city offered us—great restaurants, walkable neighborhoods, close proximity to friends. We also felt compelled to acknowledge the brokenness of our neighborhoods. We wanted to put our time and resources into making our block better, our neighborhood better. We truly felt rooted in urban life. But, the questions posed by others always sat in the back of my mind. Would we raise kids in the city? Is it even possible to stay in our neighborhood?

Both my husband, Brandon, and I grew up in suburban towns. He, a product of western Pennsylvania and the small steel mill towns that line the Ohio river; and me, a product of suburban Philadelphia. I knew strip malls and shopping centers, he knew small towns and hunting. We both loved our childhoods. We spent so much time outdoors, and knew nothing of urban life aside from a few trips into our respective cities for field trips or big sporting events. Moving to—and staying in—Philly was a shock to both of us. He came from a small public school and I went to a small, private Christian school. Then, studying at Temple University, we found ourselves in the middle of North Philly. It was a different world to us. Throughout our four years as undergraduates, we experienced tough stuff—from car thefts to a mugging, to seeing the poverty of those in the neighborhoods around our school. But, we also saw incredible beauty through the people we became connected to in those early years. When we got married shortly after college, we couldn’t imagine leaving this new place we called home. But, that was long before kids.

Both my husband, Brandon, and I grew up in suburban towns. He, a product of western Pennsylvania and the small steel mill towns that line the Ohio river; and me, a product of suburban Philadelphia. I knew strip malls and shopping centers, he knew small towns and hunting. We both loved our childhoods. We spent so much time outdoors, and knew nothing of urban life aside from a few trips into our respective cities for field trips or big sporting events. Moving to—and staying in—Philly was a shock to both of us. He came from a small public school and I went to a small, private Christian school. Then, studying at Temple University, we found ourselves in the middle of North Philly. It was a different world to us. Throughout our four years as undergraduates, we experienced tough stuff—from car thefts to a mugging, to seeing the poverty of those in the neighborhoods around our school. But, we also saw incredible beauty through the people we became connected to in those early years. When we got married shortly after college, we couldn’t imagine leaving this new place we called home. But, that was long before kids.

Table of Contents

The question of education

The Philadelphia public school system had a bad reputation. As an education student working in local schools in North Philly, I witnessed overcrowded, underfunded classrooms. I watched students arrive at school after taking multiple buses and traveling across the city alone. I heard stories of brokenness and dismay on the part of teachers. I was sure I would land a job in an urban school and “change the world.” Then, when I got an early offer from a suburban school near my hometown, I jumped on it. And, I’ve never left. As the years passed and my husband and I started thinking about having a family, I was convinced we wouldn’t send our kids to public school. Surely we could find a private school or charter that wasn’t as broken as the public school system (I felt this way, despite being a public school educator).

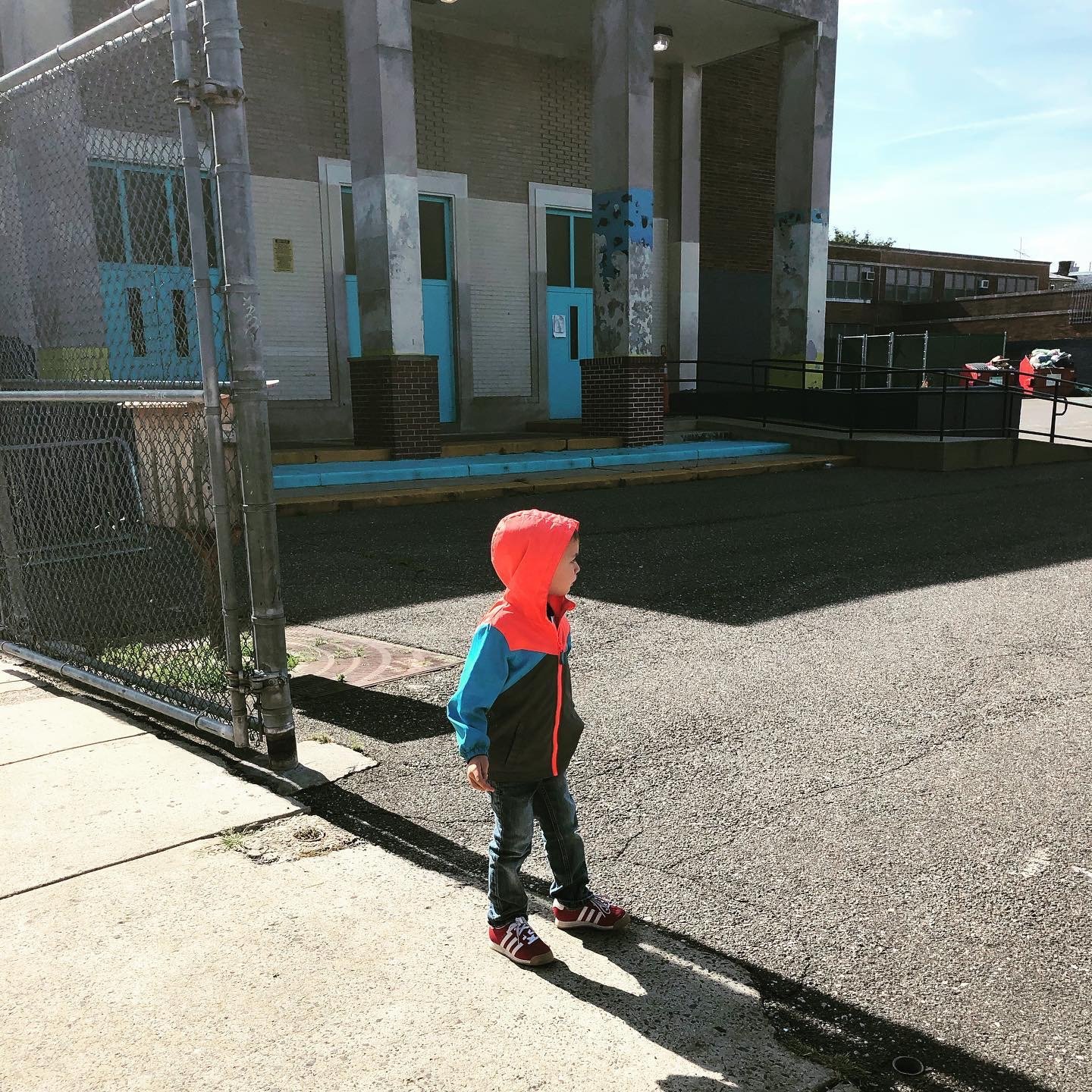

After my son was born in 2014, my mind began to change. I was diving into research on educational outcomes for students in urban environments and spent some time visiting my neighborhood school and it hit me like a ton of bricks. As I stood in the back of an old auditorium filled with parents and kids at an open house, I realized that the choice of school for my family was more than just a choice concerning my child’s education. The choice of school for my family was about the education of all kids in our neighborhood. I realize this sounds like a bold statement but it’s how I felt and still do feel. When does public education work? It works when the entire community buys into the belief that each and every student, not dependent on socioeconomic or cultural background, deserves a free and appropriate education. Every. Single. Person.

The choice of school for my family was about the education of all kids in our neighborhood.

How could I, a public school educator, champion meeting the needs of all students but assume that the neighborhood school is not good enough for my child? And, instead of looking for a perfect school that could give all the things to my child, what if I looked for a public school that I could give back to? It was at that point that I became involved with the parent group at our neighborhood school and started to find out as much as I could about the needs and opportunities there.

Let me be clear. School choice for parents living in urban centers is not an easy choice. I have friends who send their kids to private schools and charters. I have friends who home school. Their kids are thriving and I am so glad that families around me have options for education! Choosing an education for your child is such a personal decision and there is no one right answer. My parents chose to send me to a private school and I had an amazing education that I am so grateful for. The choice for public school is a personal choice because of my convictions but in no way diminishes the convictions of other parents who choose to send their kids elsewhere. I also recognize that things can change. If my son wasn’t thriving, or I felt he was unsafe in his school, I certainly wouldn’t dig my heels in on the basis of philosophy. I want him to thrive.

Still, I want to recognize that there are many families who don’t have a wealth of options for school either because of limited resources, lack of education themselves, or other hindering factors. If we, the families with options, all decide to leave public school, what happens to our local schools and the resources afforded to local students?

If we, the families with options, all decide to leave public school, what happens to our local schools and the resources afforded to local students?

It’s time to step up

Norris is halfway through his kindergarten year and loving it. His teacher is incredible and I am so thrilled with the education he is receiving. In just a few short years, this school has flipped from struggling to thriving. Parents are looking to move into our catchment (how the city divides up school placement) just to send their kids there. I am amazed at the turnaround and recognize that much of it is due to parents who decided to stay and not leave the city when their kids turned school-aged. Still, there are things my son does not have access to–programming and opportunities that are seen as a “given” in my suburban school. One of those things is music education.

Yes, I chose to send my son to a school without a full time music teacher. I assumed that this could be my contribution to his school—to advocate for music education. I tried to connect the school with pre-service teachers at Temple University to form a partnership. That didn’t work out as planned. So, I sat back and did nothing until I saw an old colleague from college. She has young children and also lives in the same catchment. And, she’s a full time elementary music teacher… in an urban, public school. “What are we going to do about getting music in the school? What can we do?” she asked. I was convicted. If not me, a teacher and professor of music education with a business meant to serve teachers and students, then who?? I set up a meeting with the principal and community program coordinator the next day.

It’s not so easy

Walking into the meeting with my son’s principal, I had two goals—to find out how choices were made regarding curriculum and “specials” classes (art, music, etc.), and to brainstorm ways to incorporate more music education into the school. The meeting was informative and hopeful, but a reminder of how much these urban schools do with so little. I learned that each school is provided funding based on the exact number of students enrolled. Schools need to send their projected numbers in the spring to receive funding for the fall. Then, elementary schools are given a designated number of “specials” based on the size of the school. The smaller the school? The less specials classes. The principal of the school needs to make the incredibly tough decision—which specials will be the most important for these students. In my son’s case, his school was given funding for four specials classes this past year. They chose to use that funding for art, gym, technology, and STEM.

Here’s the issue. If enrollment in the fall doesn’t match the projected numbers, the school district does something they call “leveling”. They move teachers from under-enrolled schools to over-enrolled schools in order to even out the teacher to student ratio. While this system to improve equity is important in theory, the reality of the shuffling can be jarring for students as teachers are removed and re-assigned each October, just as students are falling into a routine with their schooling. In my son’s case, leveling meant they lost their newly developed STEM class. Instead of four specials, they are back to three.

If the school receives funding for an additional special, music could be an option. But should it be the option? With gaps in programming, is music the most important program to add? Of course, I feel like the answer to this is a resounding YES. I probably shouldn’t be in my field if I didn’t think that way. Yet, I sympathize with the plight of his school. They are making hard decisions and constantly asking “What will be best for our kids?” I realized at that meeting that the stakeholders in this system may not know why music is so important for kids. They may not know how music education directly impacts a student’s social emotional development, well-being, and academic achievement. They may not know how a music program can change the culture of school, can promote unity, and give the school a point of pride in the community. So, now I know my task. It is my job to educate others in my community on why this matters, and, in the interim, find ways to bring more music into his school.

Moving forward

My son will not be lacking in music education. Norris is being raised by two musicians who play music constantly and involve him in musical activities. But, this may not be the case for most of the kids he sits in class with. When we advocate for kids in schools, we are advocating for all kids, not just our own. When my son hits 3rd grade, he will be able to play the violin at school (through a district-wide program in which traveling instrumental teachers go to elementary students). If he’s lucky, he might even be able to be involved in a music ensemble run by a nonprofit that visits the school. But, despite the fact that these programs reach some students in the school, they do not reach all students. If nothing changes, students in K-2nd grade will never receive regular music instruction. And, the students in the upper grades will only receive infrequent instruction from an itinerant music teacher.

My plan? First, I want to see if I can set up a partnership for the fall between pre-service teachers and the K-2 teachers at the school. I hope to find undergraduate students who want teaching experience and would dedicate one day per week to push in to classrooms and design a curriculum for these kids. Second, I want to connect Norris’ administrators with programs in Philly that are thriving, so they can see firsthand what a successful school music program looks like. Finally, I want to advocate through education—sharing research with his teachers, administrators, and fellow parents. I want to use the resources I have to advocate for the inclusion of music education in his school.

I hope to use this blog to continue to share this journey and provide updates along the way. And, if you’ve ever advocated for the inclusion of music in a school, I’d love to hear about your experience. Please share in the comments below!

Thank you for this. Far too many parents only want to go to a school where all the work is already done, never mind what happens to the other kids who are left behind. Meanwhile, the District tells us that a once-a-week itinerant music teacher giving lessons to a lucky few constitutes “having music.” Every school should have a FULL SET of specials teachers, not included in their count of regular classroom teachers. Period.

I agree, Stephanie! Thanks so much for your comment. As an instrumental teacher, I see how important it is that arts instruction happens early and often. And, it’s so sad that schools have to make these difficult decisions instead of all students having access to specials districtwide.